Former resident’s passing leaves questions

Groundwater contamination could explain cancer, other neighbors’ diagnoses

By Sheila Harris [email protected]

Thirty-year-old Springfield resident, Britney Carlo Shurtz — a former Purdy area resident and a 2005 graduate of Purdy High School — spent Christmas of 2017 in the hospital, recuperating from emergency surgery two days before.

When Shurtz, a tall, slender brunette with a quick wit and an unflappable nature, began experiencing back pain in July of that year, she chalked it up to a strained muscle and tried to tough it out. When increasing pain prompted her to seek medical treatment, her doctor prescribed physical therapy, fully expecting the problem would be resolved.

Instead, Shurtz’s pain increased.

Although an MRI could quickly reveal the source of Shurtz’s pain, her health insurance wouldn’t cover the cost until she’d exhausted other options, said her mother, Donna Carlo, of rural Purdy.

By December, Shurtz’s pain had become so intense that she could find no relief.

“Finally, the Monday before Christmas, Brit was able to get an MRI,” Carlo said. “Her doctor called as soon as he read the results and told her she needed surgery as soon as possible. Brit had a large, tadpole-shaped tumor filling her spinal cord, pressing on nerves in that region.”

After surgery to remove the tumor, Shurtz found relief from her disabling pain, but the biopsy results were grim: anaplastic ependymoma. Of the three grades of ependymomas categorized within the central nervous system, anaplastic (Grade 3) ependymomas are the most uncommon and represent the worst-case scenario. Tumors tend to rapidly recur and grow aggressively, anywhere along the length of the spinal cord, from the tail bone to the brain.

The long-term prognosis is not favorable. According to the American Cancer Society, from 2000-2016, only 948 cases of anaplastic ependymoma were diagnosed in the US in people over the age of 15.

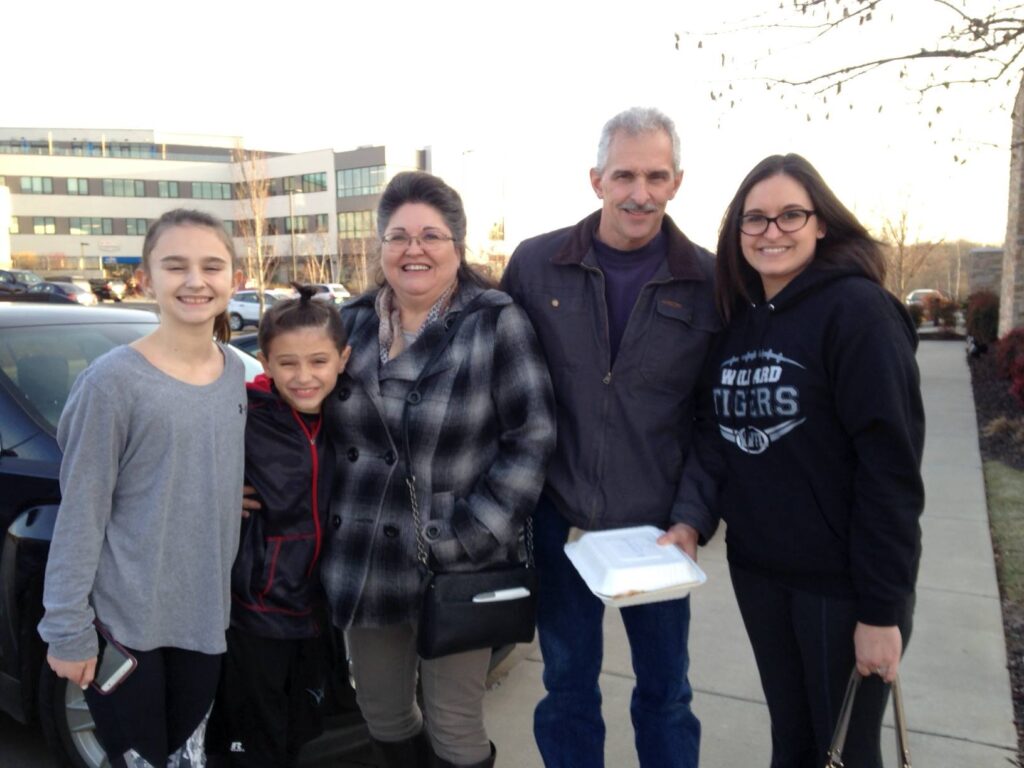

Shurtz took the news in characteristic stride. With verdict in hand, she prepared for battle for the sake of “her boys,” her husband, Zach, and their 9-year-old son, Kade.

“Everyone around her was falling apart,” Donna Carlo said. “But, Brit stayed calm. She was the voice of reason in the middle of chaos.”

The following years brought chemotherapy, radiation, more surgeries and clinical trials with experimental drugs at research institutions around the country. The most they could do was buy time; more time for Shurtz to spend with her family, more time to watch her son grow, and to attend his wrestling matches and football games.

The cause of anaplastic ependymoma is unknown. Unlike with glioma brain tumors, environmental risk factors associated with ependymomas are not well established, states a Nov. 13, 2025, study published in the National Library of Medicine.

Shurtz’s case, however, raises questions.

While in their early 20s with a newborn son, Britney and Zach Shurtz jumped at the chance to rent a brand-new duplex on West Commercial, a four-block segment of street in northwest Springfield, when it became available in 2008.

“It was a really nice location, we thought, with open [undeveloped] fields behind it, so it offered some privacy — kind of like living in the country, but in the city,” Carlo said.

City water lines weren’t installed along the street until 1997 — not long before construction on the duplexes began — said former City Utilities spokesperson, Joel Alexander.

Unbeknownst to Britney and Zach Shurtz and their families, the Tom Watkins Neighborhood upgradient to the north and east of their duplex was well-known among City and Missouri Department of Natural Resources (DNR) personnel for its proximity to hazardous waste sites.

Three miles to the west and slightly to the north of the Shurtz duplex lay the former Litton Systems site, currently owned by Northrop Grumman, where, from 1964 through the early 1980s, Litton employees had dumped the industrial solvent trichloroethylene (TCE) into unlined lagoons and sinkholes on the property, after using the chemical as a cleaner on the circuit boards the company manufactured. With oversight by the DNR, the sampling and remediation of groundwater and soil on and beyond the property is ongoing.

By the end of 2023, approximately 998.5 pounds of [TCE] had been removed from the groundwater since groundwater extraction systems began operating in June 2019.

TCE is considered a known human carcinogen by the Department of Health and Human Services (DHSS) and the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) characterizes the solvent as carcinogenic to humans by all routes of exposure, with “effects to the liver, kidneys, and immune and endocrine systems [observed] in humans exposed to TCE occupationally or from contaminated drinking water.”

Chronic exposure to TCE by inhalation also affects the human central nervous system, cites the same EPA document.

In some areas of the country, a three-mile separation between the Shurtz home and a toxic waste site would make contamination unlikely. However, in the Ozarks fractured karst hydrogeology — riddled with sinkholes, caves, losing streams and springs — contaminants in groundwater can travel rapidly. TCE has been detected in monitoring wells on and off the Litton property, including a site four miles to the east, where the DNR is searching for its source.

According to the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR), as reported in 2016, TCE is the most frequently reported organic contaminant in groundwater.

Shurtz learned of the Litton site’s pollution of groundwater in early 2018, shortly after her cancer diagnosis, when news broke that TCE vapors from Litton had infiltrated Fantastic Caverns, a commercial cave located four miles north of Springfield. Wondering if her cancer diagnosis could be connected with possible exposure to Litton’s waste, Shurtz and her family moved to another area of Springfield a year or two later, after living at their West Commercial Street address for almost 10 years.

After moving, Shurtz recalled a site much closer to her previous home, a more likely source of pollution, she thought. Her aunt investigated.

Three blocks northeast and upgradient from the former Shurtz home, a chain-link fence, with posted notices that the site within was subject to a Hazardous Waste Management Permit, encircled a 68-acre property.

Official records for the site, located at 2800 West High Street, read like a serial saga, with the ending still anybody’s guess.

The American Creosote Corporation and its successor, the Kerr-McGee (KM) Corporation (operating at times under different names) pressure-treated railroad ties with creosote on the property, from 1907-2003. For the majority of those years, personnel dumped creosote process waste into unlined lagoons on the site, which lies along a “peak” or “divide,” above the surrounding terrain.

As is common in the Ozarks, the waste did not remain where it was “stored.” The creosote sank, partially dissolved and migrated through soil and fissures in the karst bedrock, into groundwater, then traveled on and offsite in diverse directions.

Under the federal Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA), the former KM site is now considered a Closed Hazardous Waste Disposal Facility.

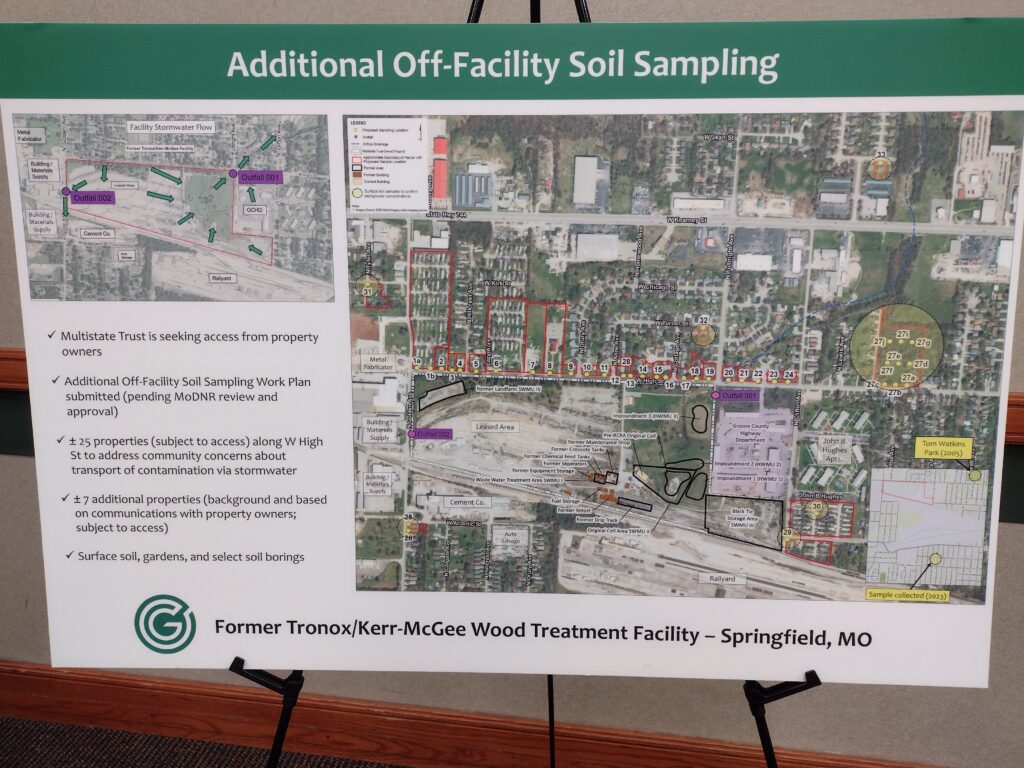

The site is now owned by the Greenfield Environmental Multistate Trust (the Trust) as the result of judicial appointment in 2011, following a bankruptcy settlement with a KM spinoff company, Tronox. Under the auspices of the Trust, with oversight by the DNR, the site has been, and continues to be, the subject of ongoing testing and attempted remediation of soil, air and groundwater, both on and beyond the property.

In July 1992, soil and groundwater samples showed contaminated groundwater plumes extending off the property, to the northeast and to the south.

The Trust maintains a network of 88 monitoring wells from which periodic water samples are drawn in an attempt to determine whether groundwater contaminant plumes are increasing or decreasing.

Production at the KM facility ceased in 2003, but recovery wells continue to operate on the property around the clock (barring glitches), in an attempt to contain and alleviate groundwater contamination and capture creosote.

Contaminants of concern (COCs) from the KM site include, among other chemicals, Benzene, Toluene, Ethylene, and Xylenes and Naphthalene.

Aside from the chemical cocktail, the long-term side effects of Benzene, on its own, according to Drugwatch.com, include aplastic anemia, blood disorders [including leukemia], cancer, chromosomal abnormalities, excessive bleeding, reproductive issues and a weakened immune system.

Exposure to Benzene can occur through inhalation of airborne emissions (sometimes from vapors released upward through soil from groundwater), through oral ingestion, and through skin absorption by contact with contaminated water.

Although the EPA established a maximum permissible level of Benzene in drinking water at 5 parts Benzene, per billion parts of water (5 ppb), some scientists believe there is no safe exposure level.

“The Multistate Trust has removed more that 114 million gallons of water (about 8.7 million gallons a year) and 7,500 gallons of creosote from the ground (subsurface) since 2011, as part of the ongoing cleanup,” Multistate Trust Springfield program director, Tasha Lewis, stated in an email to the Cassville Democrat in November 2025.

Attempted remediation at the KM site began in 1976, four years after a creosote-like substance was spotted surfacing in nearby Vich Spring after heavy rains. No attempt was made (in 1972) to determine the substance’s origin, until after environmental laws were passed in 1976, state DNR records. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) then tracked the substance back to the KM facility.

New production methods and different waste-disposal means were implemented, but the pressure-treating of ties continued, until production ceased in 2003.

In 1990, the EPA developed the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) Storm Program in response to 1987 Amendments to the Clean Water Act, which require permits industries in several categories, including hazardous waste management. Per the new requirements, KM constructed two stormwater outfalls (a third was later added) which directed stormwater off the property to the northeast and to the west.

Outfall No. 2, on the west side of the property, directed stormwater downhill to the south and southwest, toward the Shurtz property and the Wilson’s Creek drainage, beyond.

Stormwater outfalls, per NPDES regulations, are checked quarterly for COCs.

According to Trust documents filed with the DNR, a historic flooding event occurred in the neighborhood in June, 2017. Afterward, Outfall No. 2 contained elevated levels of Total Suspended Solids (TSS) — particles of debris to which toxins from the facility (if they were present) could attach and hitch a ride.

Shurtz first began experiencing the back pain that later proved to be cancer in July 2017 (one month after the June flooding event), Carlo said.

According to Trust documents, in December 2020, northwest Springfield experienced another major rain event while a cracked sewer main and sewer lines to the KM facility were being replaced by City employees. Outfall No. 2 again contained elevated levels of TSS.

The cracked sewer main adjacent to the KM facility was discovered in September 2020, when City employees smelled, then spotted, sewage emerging from a stormwater outfall. It isn’t clear how long the sewer main had been cracked before the sewage was spotted, but the damage could have allowed sewage to infiltrate ground and surface waters, Trust documents indicate.

Remediated groundwater from both the Litton and the former KM facility are released into the Springfield sanitary sewer system.

The recovery-well system at the KM facility was offline between October 30, 2020, and April 15, 2021, while the City replaced sewer lines.

In July 2023, five-and-a-half years after her initial diagnosis, Britney Shurtz laid down her sword, choosing not to fight a brain tumor that had grown too large to safely remove by the time it was discovered.

“Brit had a total of 28 different treatments (including multiple surgeries) during five-and-a-half years,” Carlo said.

Not once did Shurtz give in to despair.

“The outcome is in God’s hands,” Shurtz said often, from faith that remained steadfast until she drew her last breath.

Her example of faith, on its own, will stand as Shurtz’s legacy. With her courage in the face of adversity, she cleared the way for her family and close friends, showing them how the path should be traveled.

However, her passing may also serve the purpose of alerting prospective tenants and home-buyers to the importance of researching the surrounding area prior to renting or purchasing. Currently, there are no laws in Missouri requiring the disclosure of nearby hazardous waste sites.

In 2024, a year after her niece’s death, Shurtz’s aunt learned that other residents on West Commercial Street had been diagnosed with illnesses that could also be associated with exposure to chemicals. Jan Goosey, 74, was diagnosed with a rare autoimmune liver disorder two years before, and another neighbor’s child had been diagnosed with leukemia at about the same time. Yet another neighbor, who lived two blocks northeast of the Shurtz home (and nearer to the KM site), had been diagnosed with an autoimmune disorder that affects the central nervous system during the same time frame.

Many neighbors to the north and east of the facility, Shurtz’s aunt also knew, had experienced health anomalies, although many of theirs had occurred while the facility was still operational.

The serious health issues among the handful of neighbors in close proximity to the former Shurtz home, all of which could be associated with chemical exposure, seemed, to Shurtz’s aunt, to be more than a coincidence.

The Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services (MDHSS) initiated a cancer study of the neighborhood, focused solely on anaplastic ependymoma, the specific (and rare) type of cancer that Shurtz had been diagnosed with. Other types of cancers and illnesses were not taken into consideration.

“I felt like the cancer study was only designed to pacify me, not because of any concern for other neighborhood residents,” Shurtz’s aunt said.

Tracking contaminants in karst can play out like a game of cat-and-mouse, with detectives often on the losing end, Shurtz’s aunt knew.

Some happenings defy explanation, cancer diagnoses included. Individual variables stack the deck, including genetic factors, length of exposure to toxins, incubation periods, a person’s lifestyle and the strength of a person’s immune system.

“Brit was always susceptible to issues with water,” Donna Carlo said. “She quit wading in the creek when she was young because she’d break out with red bumps on her feet. Nobody else had a problem.”

Since the Trust assumed responsibility for the KM site in 2011, most of the remedial focus of the project has been along a northeasterly trajectory from the facility, in the direction of Fulbright Spring, a public drinking water source. Samples from several monitoring wells in that direction consistently show contaminants of concern above Groundwater Protective Standards (GWPS), although no facility-related contaminants above health limits have been found in Fulbright, Lewis said.

In comparison to the area along the Clifton drainage to the northeast of the facility, scant attention has been paid to areas to the southwest of it, where groundwater and surface water drain southwesterly toward the former Shurtz home and Wilson’s Creek.

Of two monitoring wells installed in the residential area southwest of the facility a few years ago, one was dry, and the second showed no contaminants of concern above GWPS. Trust personnel decided no further testing was needed, even though the possibility of downward percolation and flow of contaminants in that direction could, in theory, still exist.

Based on a tip, Shurtz’s aunt took a closer look at the neighborhood south/southwest of the facility in 2024.

She discovered that an Environmental Site Assessment (EA) had been performed on a property that revealed the presence of five Underground Storage Tanks, installed in 1975 and closed in place — contents included — sometime before state tank-closure regulations were established in 2004. Two of the tanks contained solvents, one contained petroleum, and two others were reportedly empty. The tanks, stated the results of the EA, posed a direct threat to properties to the south if they were to leak.

According to industry experts, the single-walled steel tanks used in 1975 are subject to corrosion and typically have no more than a 30-year lifespan.

To complicate contaminant-tracking, if the tanks south of the KM site were to leak, their analytes would be the same as those of KM’s hazardous releases, Ken Koon, then-director of the DNR Tanks Division, told the Cassville Democrat in 2024.

In October 2024, Lewis took a walking tour of the neighborhood where Britney Shurtz had once lived. Lewis looked at the site where the five solvent tanks were buried, and she spoke with Shurtz’s neighbor, Jan Goosey, who explained how stormwater impacted the property after major rain events, how it descended from streets above and pooled across the backyards of the duplexes, before subsiding and wending southwesterly.

“Kade and I used to get out and play in the stormwater-lakes in our yard after it rained,” Shurtz once told her aunt.

The neighbor two blocks northeast of Shurtz, who was later diagnosed with an autoimmune disorder, played in the pooled stormwater with her son, too.

After the tour, Lewis made plans to sample the soil in the yards of two residences to the south of the facility’s Stormwater Outfall No. 2, where stormwater exited to the west and made its way south along Golden Avenue, in the direction of the former Shurtz home.

That soil sampling never happened.

“I wasn’t able to get the property-owners’ permission,” Lewis said in November 2025.

She implied that no further attempts would be made.

While a concrete answer regarding an environmental source of Shurtz’s cancer will likely never be pinned down, multiple possibilities have been unearthed, including contaminated stormwater; contaminated ground or drinking water; pollution from leaking storage tanks; and the release of toxic vapors from soil contaminated with more than 100 years of run-off from the KM facility — perhaps unearthed when the West Commercial Street duplexes were constructed in the previously undisturbed field in the Wilson’s Creek drainage.

Carlo questions why Springfield officials ever allowed residential housing to be built so near a known hazardous waste site.

“It’s got to be about money,” she said.

Most of the residences located nearest to the former Kerr-McGee facility are income-generating, rental properties, and most were constructed prior to Hazardous Waste Management legislation enacted in 1976.

Neither Britney Shurtz nor any of the neighbors her aunt spoke with were aware that an ongoing hazardous waste remediation site existed so close to their homes. Current law does not require that landlords disclose such sites.

Britney Shurtz said that if she had known about the nearby contaminated site before she and Zach signed a lease, she would never have moved into that neighborhood.

Kimberly Mullins, a former resident of the John B. Hughes apartment complex to the east of the KM facility, said she didn’t have many options when she moved into her apartment.

“It would have been nice to be able to make an informed decision, though,” Mullins said.