Melissa Hamilton: The rise of native plant and companion gardening

In 2025, gardens are undergoing a quiet revolution.

Across backyards, parks and public spaces, more people are replacing exotic ornamentals with native plants — and pairing them strategically using companion planting techniques.

This movement, once niche and conservation- driven, is now shaping how home gardeners, landscape designers, and municipalities think about beauty, biodiversity, and resilience.

Native plants are becoming the new standard because they offer something traditional landscaping often lacks: self-sufficiency. These species have adapted over centuries to their local climate, soil, and wildlife. In Missouri, for example, coneflowers, milkweed and prairie grasses thrive in extreme summer heat without supplemental watering or fertilizers.

Gardeners are drawn to native species because they reduce maintenance while increasing ecological value. In a time of rising water costs and unpredictable weather, these tough, drought-resistant plants are both practical and sustainable.

But native gardening isn’t just about plant selection — it’s about rethinking the entire layout and purpose of a garden. That’s where companion planting comes in. Companion planting is the practice of growing different plants in proximity to enhance each other’s growth and health. This can take the form of pest deterrence, improved pollination, better use of soil nutrients or simply maximizing visual appeal.

For example, pairing purple coneflowers with bee balm and blazing star creates a layered effect of height, color, and bloom time. While the coneflowers draw bees in early summer, the blazing star picks up in late summer, ensuring continuous nectar sources. Meanwhile, the bee balm’s scent helps deter unwanted pests while attracting hummingbirds.

These companion strategies mimic natural ecosystems, creating plant communities that function better together than alone.

The resurgence of interest in these methods is being driven by a blend of environmental awareness and evolving aesthetics. Gardeners are moving away from manicured lawns and rigid formal beds in favor of more dynamic, layered plantings. What was once called “messy” is now being rebranded as “meadow-inspired” or “chaos gardening.”

In this style, intentional plant pairings create vibrant, semi-wild scenes that benefit pollinators and people alike.

Designers and homeowners alike are also turning to companion planting as a chemical-free solution to garden challenges. Instead of spraying for pests, they plant deterrent species like milkweed or goldenrod. Instead of synthetic fertilizers, they mix nitrogen-fixing plants or deep-rooted natives that pull nutrients from below. As ecological landscaping gains momentum, companion planting becomes more than just a method — it becomes a mindset.

In Missouri and beyond, the fusion of native planting and companion strategies is proving especially effective. Native species not only thrive in local conditions but also support specific local wildlife. Monarch butterflies rely on milkweed to lay their eggs, while certain bees depend exclusively on native flowers. By combining natives that bloom at different times and grow in harmony, gardeners can provide food, shelter, and structure to insects, birds, and other wildlife throughout the growing season.

This shift reflects deeper cultural values. The popularity of native and companion gardening reveals a collective desire for gardens that are not just beautiful, but meaningful. These gardens do more — they conserve water, feed pollinators, support biodiversity, and reestablish our connection to place. In essence, companion planting with natives is about rebuilding balance: between beauty and function, tradition and innovation, people and nature.

What was once an alternative gardening philosophy is now moving into the mainstream. In cities, native plant ordinances and pollinator pathways are taking root. In suburbs, homeowners are trading lawn for wildflower borders. And in rural areas, farmers are reintroducing hedgerows and planting strips of native flowers between fields.

Together, these changes are redefining what it means to “garden.” It’s no longer just about what looks good — it’s about what works well and lives well. Native plants and companion planting are not only the future of gardening; they’re a return to what the natural world has always known: diversity is strength, and cooperation sustains.

List of common Missouri natives for sunny location by primary plant, good companions and benefits:

• Butterfly Milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa); Coreopsis, Coneflower, Little Bluestem; Attracts monarchs & pollinators; drought-tolerant

• Purple Coneflower (Echinacea purpurea); Milkweed, Bee Balm, Blazing Star; Deep-rooted; pollinator magnet

• Black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta); Prairie Dropseed, Coneflower, Aster; Deer-resistant; long blooming

• Bee Balm (Monarda fistulosa); Echinacea, Goldenrod, Milkweed; Attracts hummingbirds & beneficial insects

• Blazing Star (Liatris pycnostachya); Coneflower, Prairie Clover, Coreopsis; Tall vertical accent; butterfly host

• Joe Pye Weed (Eutrochium purpureum); Swamp Milkweed, Turtlehead, Boneset; Late bloomer; strong pollinator support

• Coreopsis (Coreopsis lanceolata); Milkweed, Wild Petunia, Blazing Star; Early nectar; supports native bees

• Wild Petunia (Ruellia humilis); Coreopsis, Aster, Wild Strawberry; Groundcover; soft filler; supports insects

• Big Bluestem (Andropogon gerardii); Blazing Star, Coneflower, Rattlesnake Master; Tall structure; bird habitat; weed suppression.

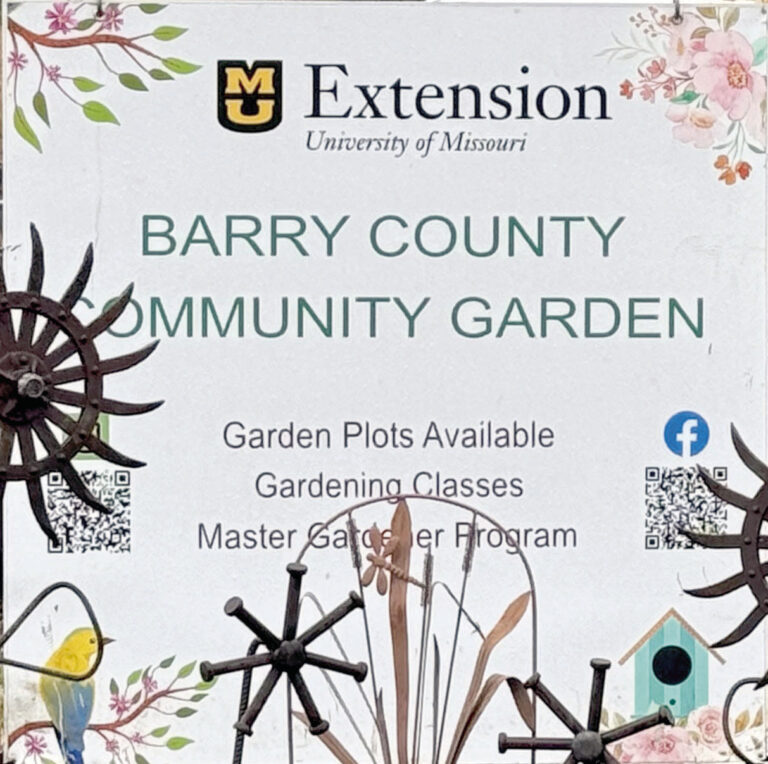

Melissa Hamilton is a dedicated volunteer with the Barry County Community Garden and a Barry County Master Gardener. She may be reached at melissa.hamilton1969@ gmail.com.