Parents, colleagues remember youngest member of dive team

Oct. 14, 2022, dawned crisp and clear – a chilly 37 degrees, with temperatures forecast to rise into the mid-70s.

The sun was barely cresting the eastern ridge, and mist still clung to the mill pond as members of the KISS Rebreathers dive team gathered at the walkway to Roaring River Spring to firm up their morning’s dive plan.

Light spirits accompanied anticipation of the perfect fall day ahead. Jokes followed the sighting of each other’s clothing, a motley mix of cold and warm weather attire.

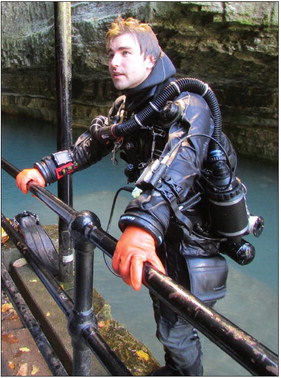

Eric Hahn, 27, the youngest member of the team, wore a winter jacket and stocking cap pulled down firmly over his thick, wavy brown locks, while his lower extremities were clad only in shorts and sandals. The discrepancy was not lost on his teammates, who pointed out that at least fellow diver, Jon Lillestolen, wore socks and running shoes with his shorts and winter coat.

Hahn took the light-hearted ribbing in stride and responded with his usual smile, knowing his street-clothes would soon be replaced with his new cherry- red drysuit, a color which reflected his upbeat personality.

Optimism prevailed among the divers that Friday morning. If visibility proved good below the 225-foot-deep restriction in the cave, the following day’s dive might include a push beyond the 472-foot depth-record they’d achieved in November 2021.

KISS Rebreathers CEO and team leader Mike Young doesn’t allow himself to become excited about the possibility of breaking records, he said. Caution should always prevail.

“Underwater, you have to always be present in the moment,” he said. “If you start thinking ahead, it’s too easy to lose your focus on what’s happening around you.”

The dive plan was to stage safety cylinders in Roaring River Cave along the route of a possible second, record-breaking depth. Some 14 or more tanks, premixed with appropriate levels of oxygen, helium and nitrogen for their intended depths, would be staged and available for divers to use in case of emergency.

Divers paired off in the buddy system used universally as a safety net for divers, should something not go as planned in the unforgiving, underwater world.

Divers 1 and 2 entered the water at 10:58 a.m. and carried safety cylinders below the 225-foot restriction, where they secured them to guidelines and ascertained that visibility was clear below 300 feet, then swam back up through the restriction.

At 11:12 a.m., Diver 3 entered the water with Hahn to begin the duo’s assignment of staging safety cylinders at 130-foot and 190-foot depths. As they reached a depth of 190 feet, they encountered Divers 1 and 2, who were on their way back up to serve their decompression time. Cheery greetings were exchanged, and, as a fellow diver later reported, they broke into a moment of song, a hearty rendition of the theme to Indiana Jones.

“I couldn’t help smiling,” the listening diver said.

As Divers 1 and 2 continued their ascent, Hahn and Diver 3 secured safety cylinders to the guideline at the 190-foot depth. As Diver 3 was preparing to ascend, Hahn suddenly bumped into him, hard, in a manner that alerted Diver 3 that Hahn was having a problem.

He was. Diver 3 began desperate rescue efforts, then summoned Diver 2, who was the nearest diver available to render assistance. Both of their efforts proved unsuccessful.

Hahn took his last breath at approximately 11:25 a.m., according to the accident analysis report published in first week of January by the National Speleological Society Cave Diving Section (NSS-CDS).

His body was recovered from a 200-foot depth in the spring and brought to the surface by his fellow divers at 4:24 p.m., where it was received by the Barry County Coroner.

His death leaves a void.

Hahn was the second-born of twin first-borns for Gordon and Linda Hahn, of Charlottesville, Va.

“Alexander was born one minute before Eric,” Linda Hahn said. “But, Eric did everything first after that. He sat up first, he walked first, and he mastered skiing first.”

“But, not by much,” said Eric’s father, Gordon Hahn, who regularly took the twins to Wintergreen Ski Resort, about an hour from their home.

“They were on the beginner slopes when they were only four or five,” Hahn said. “Eric ‘got it’ first, but Alexander got it on our next run down the slope.”

The entire Hahn family – including younger son Dylan and daughter Heidi — took up scuba diving when the children were old enough to begin taking lessons from Linda’s brother, who lived in Maui. It was a skill that suited and enhanced Eric’s love for exploration, a passion that all who knew him have commented on.

Hand-in-hand with exploration was Eric’s love for engineering, his mother said.

Hahn was part of a robotics team in high school, a team he was instrumental in forming and which won competitions against college teams. After graduation from Albemarle High School in Charlottesville, Hahn moved to Blacksburg, Va., to pursue a degree in Engineering from Virginia Polytechnic Institute (Virginia Tech or VPI).

In Blacksburg, he became part of the VPI Cave Club, an organization for Virginia Tech students interested in Speleology and the exploration of the many dry caves in the surrounding area. He also became involved with an animal rescue organization and joined the Blacksburg Volunteer Rescue Squad, where his caving skills were often called upon to rescue humans.

While Hahn was still an engineering student at Virginia Tech, he was hired by Torc Robotics, a pioneer in autonomous vehicle technology. There, he played a part in the creation of a self-driving eighteen-wheeler.

KISS Rebreather Diver Jon Lillestolen, also of Blacksburg, doesn’t know exactly when Hahn took his initial cave-diving classes.

“I do know he was bitten hard by the cave-diving bug,” Lillestolen said. “After our first meeting, and after doing some dry caving with Eric, I knew he was interested in cave-diving, and he slowly went through the training progression. After he finished his full cave class and other decompression classes, we started doing a lot of dives together.”

After Hahn gained cave-diving experience, he and Lillestolen often set off as a team to explore previously unexplored underwater cave systems in Virginia, a passion they held in common, but one too dangerous to pursue alone.

On Hahn’s first trip to Roaring River Spring in October 2021, he served as a “tank monkey” for members of the KISS Rebreathers dive team, a role in which he helped set safety cylinders prior to a dive, then helped retrieve them from the spring later. Hahn enjoyed participating, and he never missed an opportunity to pause and smile for the photographers who were present. His effervescent personality was contagious, and one couldn’t help but be happy when he was around.

“I loved him,” said Mike Young’s wife, Sheri, who has children approaching Hahn’s age.

His team members are devastated by his loss.

Diver 2 admits to breaking down after recently hearing strains of the Indiana Jones theme.

“We’ll always have moments that will trigger our memories of Eric,” the diver said.

Diver Gayle Orner admitted to some reservations about going back into Roaring River Spring again the day after Hahn’s death to help teammates collect the equipment that had been staged the day before.

“I forced myself to participate in the collection dive, even though Mike told me I didn’t have to,” she said. “During that simple 15-minute dive, I found that I experienced the same sort of peace that I always feel while cave-diving. I wanted to spend more time there.”

After losing his Virginia caving partner, Lillestolen has not participated in any dives since October, other than a previously scheduled training session.

“I do a lot of running, now,” he said.

Diving’s not off the table, he said. He just hasn’t planned any trips.

The accident analysis report attributes Hahn’s death to seizures caused by central nervous system oxygen toxicity. Due to discrepancies between his cylinder labels and post-accident analyses, it is believed that Hahn mis-analyzed the mix of gases in his cylinders, which contained oxygen levels much higher than were recommended for his planned dive of 190 feet. Each of the divers are responsible for analyzing the mix in their own cylinders, then must report that number to the surface manager prior to diving.

Although to the lay-person oxygen sounds beneficial, when under pressure, it becomes more potent, which can make it toxic, resulting in loss of sensory functions, followed by seizures.

The report also notes that Hahn did not have helium in his cylinders, a necessary part of a gas tri-mix for depth divers. The helium offsets the nitrogen, which, at depth, can cause narcosis resulting in muddled thinking.

Hypercapnia, or a build-up of carbon dioxide, could also have exacerbated the effects of too much oxygen, the report stated.

“We’ll never know why Eric chose to dive with the tank-mixes he had,” said diver Randall Purdy. “But, I do know most of us who have reached a certain level of cave-diving experience have made some bad decisions in the past. Those of us who have survived quickly changed our ways.

“I think Eric had become so comfortable with what he was doing that he didn’t have any idea of the danger he was in.”

While the NSS-CDS reports says it’s uncommon for a diver to have an oxygen seizure with the short exposure that Hahn had, Young said each diver’s tolerance for elevated oxygen levels varies.

“It’s weird,” he said. “There’s no constant. Somebody’s tolerance might be lower simply because they didn’t get enough sleep the night before or because they had too much coffee that morning.”

It is not known whether Hahn had any pre-existing, undisclosed medical conditions that might have played a part in his lower oxygen-tolerance threshold.

Hahn’s KISS Sidewinder rebreather was determined to be intact and functioning properly.

Young is applying for a renewed permit for the KISS Rebreathers team to continue their exploration of Roaring River Spring in 2023.

“If we’re approved, we’re working on mitigations to our safety measures,” he said.

Linda and Gordon Hahn have expressed hope that the KISS team’s exploration of Roaring River Cave — work they said Eric loved — will be allowed to continue in 2023. They also said they would like to return to Roaring River Spring, maybe in October.