Shell Knob sculptor contributing to Fort Marion project

By Sheila Harris

sheilaharrisads@gmail.com

After European immigrants settled into the new world, which later became the United States, they cast their eyes upon the land where the indigenous natives hunted and gathered — they saw that it was fair.

“That land could be ours,” our European forebears must have thought, and, by passing legislation and using brute force for well over a century, they wrested the ancestral homes of the Native American tribes from beneath their feet. The relative newcomers forced the natives westward, initially, with promises of land reserved especially for them, to live on as they pleased. The promises, however, proved to be conditional, and tribal members consistently became the victims of crimes against humanity.

Lew Aytes, who lives near Shell Knob with his wife Kathryn, has been selected as the sculptor on a team of artists, writers, museum and university representatives and Native Americans, who plan to shine light into one corner of that dark history with a wide-ranging project named “Calling Back the Spirits.”

The goal of the project is to preserve by art and the written word what was previously learned only through the oral recounting of the story of Fort Marion by the descendants of the victims.

“Now, a lot of the descendants haven’t even heard the story,” Aytes said.

Outside of the tribes, the story is almost unknown.

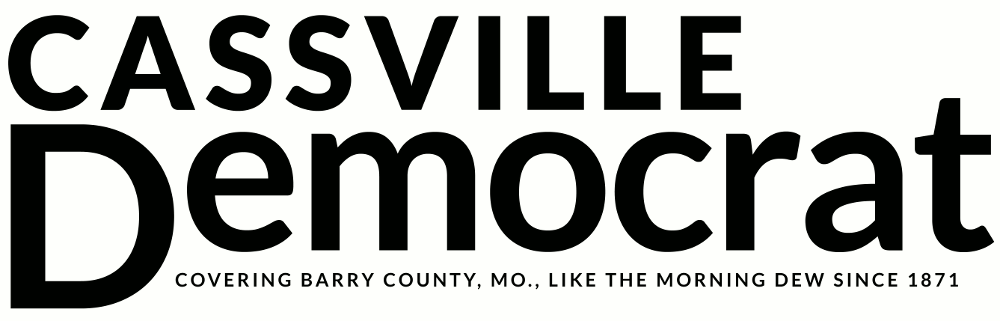

Arrested in 1875, when European settlers were pushing westward into the Great Plains and meeting with resistance and attacks from the natives, 72 members of five Plains Indian tribes – The Cheyenne, The Kiowa, The Arapaho, The Comanche and The Caddo – were singled out for captivity.

“They were either leaders of their tribes, or individuals who the military thought would cause problems for settlers,” Aytes said.

From Camp (Fort) Sill in Indian Territory (Oklahoma), the captives were put on a train bound for Fort Marion, an old Spanish fort near St. Augustine, Fla., that had been reopened to house Native American prisoners. Today, it is known as Castillo de San Marcos.

“The prisoners were chained together and shackled to the walls of freight cars in a seated position,” Aytes said.

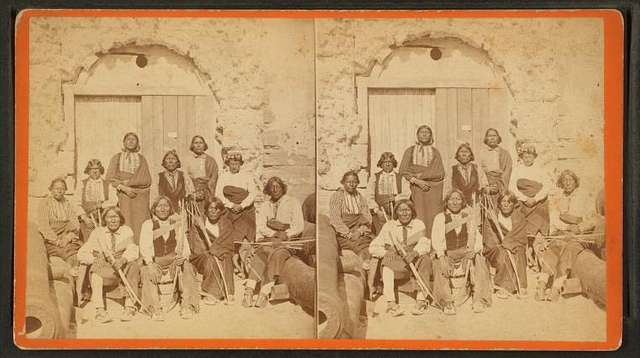

It wasn’t just warriors who were on the freight cars, said Aytes. The wives and children of some warriors refused to have their families separated, so they jumped onboard as well.

Instead of a direct route to Fort Marion (1,229 miles), Lt. Richard Henry Pratt, who had been put in charge of the prisoners, opted for a much longer northerly route.

“Pratt was always looking for ways to profit from the prisoners,” Aytes said, “So, the train stopped at every major city along the way, where eager residents paid money to gawk at them.”

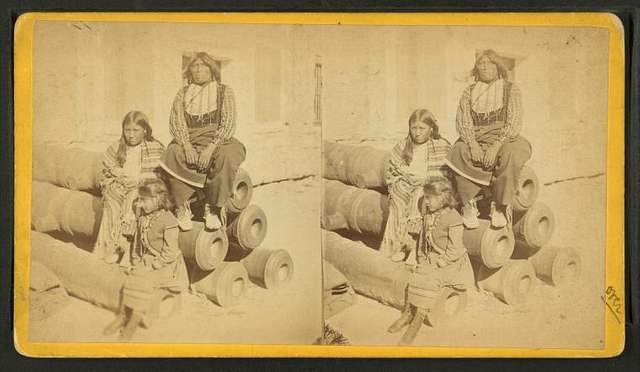

Pratt believed in assimilating Native Americans into the European settlers’ culture by teaching them the ways of the white man. Reservations, he believed, wouldn’t serve that purpose, so when the train arrived at Fort Marion, the prisoners’ hair was cut and they were forced to don the clothing style of their captors: military uniforms. They were also required to learn English, and the adoption of Christianity was strongly encouraged.

“Kill the Indian; save the man,” was Pratt’s motto, one which he rigorously attempted to enforce.

In later years, one of Pratt’s pet projects became the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, which he founded in Carlisle, Penn., in 1879. There, over a period of 39 years, some 10,000 Native American children from over 140 tribes were removed from their families and placed in residence at the boarding school, where they learned the culture of the European-Americans, suffering trauma in the process. Heralded a success by the U.S. military, who funded it, the Carlisle School became the model for many more such schools to follow.

“The Native American prisoners in Fort Marion were expected to earn money for their keep,” Lew Aytes said. “One way they could do that was by creating artwork. Twenty-six of the prisoners were artists, so they were provided with used ledgers, upon which they drew. Most of their drawings depicted daily Native American life, which often included scenes from hunts and battles. They were able to sell their artwork to outsiders to pay for their keep, plus have a little extra to send home for their families.”

Those prisoners who were not artists were put to work in other ways which might turn a profit, including the polishing of shells to sell to tourists. The group was also forced to perform their cultural dances for white spectators, who paid money to watch them.

One of the greatest indignities came in 1877, when Pratt allowed the captives to be the subject of an experiment in the pseudo-sciences of phrenology and craniology, for the purpose of attempting to prove that Native American skulls were inferior.

Sculptor Clark Mills was commissioned to create plaster casts of the prisoners’ heads, front and back, using a technique both uncomfortable and terrifying. A tight skull cap was placed over their heads, straws were inserted into their nostrils for breathing purposes, and plaster was applied, where it remained until it was set. The plaster was removed in two sections, then reconnected in one piece to form bodyless heads, which bore a remarkable resemblance to those who were subjected to modeling for them.

Pratt himself had his head cast first, in order to reassure the captives.

In 1878 — three years after their incarceration — 63 of the prisoners were released to return to their families without ever being charged or tried for anything. One prisoner died on the train to Fort Marion while trying to escape, and eight died from tuberculosis, suffered due to the the dank, cave-like confines of the prison.

Of the 63 remaining prisoners, all eventually made their way back to Indian Territory (Oklahoma). A few maintained the newly assimilated culture of the white man, while others returned to their tribal traditions.

Although the warriors themselves have long since passed, their plaster likenesses remain, stored on shelves in backrooms of the Smithsonian and Peabody Museums, where they stand as disturbing monuments to man’s inhumane treatment of his fellow man.

Curators have long been uncertain of what to do with the body-less plaster heads.

“Because they were not created by Native Americans, they do not fall under the legal requirements of the NAGPRA (Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act), enacted in 1990,” Lew Aytes said.

Enter the project, “Calling Back the Spirits.”

In his role as sculptor for the project, Aytes is casting replicas and creating busts of 15 tribal members who were held captive in Fort Marion, using their original plaster “life-masks” as his basis.

“Each of the five tribes will be represented,” Aytes said.

The replicas, after casting, will be bronzed, Aytes said.

In addition to busts of 15 of the prisoners, Aytes will sculpt likenesses of five living descendants of the prisoners, including the 6-year-old granddaughter of Dr. Dolores Subia BigFoot, a childhood trauma specialist in the University of Oklahoma Health and Sciences Center. BigFoot, a member of the Caddo Nation, is a descendant of the only Caddo warrior taken captive. Her granddaughter, however is a descendant of both Caddo and Cheyenne warriors.

Dr. BigFoot’s late husband, John Sipes, Jr., was a Cheyenne Chief and a historian for the Cheyenne tribe. Sipes collected stories of the Fort Marion prisoners of war for over three decades and willed his collection to his and Dr. BigFoot’s son, Ah-in-nist Sipes.

Dr. BigFoot and Ah-in-nist, who recognize the impact of generational trauma, first had the idea for the “Calling Back the Spirits” project.

In addition to educating tribal nations and the general public about the Fort Marion prisoners of war, the project is intended to promote understanding and healing among the nations whose ancestors were held captive.

“It was an honor for me, as a white American, to be chosen as the sculptor for this Native American project,” Aytes said.

Aytes, after leaving a career in finance, has been a professional sculptor for over 30 years. His specialty creations are busts and reliefs of Indigenous people, as well as sculpted portraits of historical figures. Aytes was selected by the Missouri Arts Council as a featured artist in May, 2023.

In addition to Aytes’s sculptures for the “Calling Back the Spirits” project, two books will be written by other members of the team: one is a pictorial, coffee-table book, and the second is a children’s book. The exhibit will also include storyboards, video interviews with descendants and a documentary of the history of the Fort Marion prisoners.

When the elements of “Calling Back the Spirits” are complete, they will become part of an international museum tour, including The Smithsonian and The Peabody Museum, where they will be displayed in conjunction with the museums’ own collections. A permanent exhibit will be housed in a national museum and will be available through links to an e-Museum.

The Peabody Museum has agreed to loan a few of the original life-masks of the Fort Marion prisoners for use in the exhibit. The masks were formerly reserved only for the eyes of museum personnel and descendants of the prisoners.

“When the museum tour is finished, the original plaster life-masks will be given to living descendants of the prisoners,” Aytes said.

Then, their spirits will finally be home.

Aytes said the “Calling Back the Spirits” tour is expected to begin in late 2025.